Gregory William Mank is a prolific Hollywood horror historian, writing numerous books on the subject. The Very Witching Time of Night: Dark Alleys of Classic Horror Cinema, published 2014, chronicles an variety of topics from the Golden Age of Hollywood horror (1930s-1940s). As Mank states in the introduction, the genesis of the book stemmed from his desire to tell “tangential material” to his other, more focused topics; material that “cried out for its own focus and attention.” Therefore, instead of a book solely dedicated to the Universal Frankenstein series, or women in horror films of the 1930s-1940s, The Very Witching Time of Night dedicates singular chapters to a vast array of Hollywood characters, stories, and film productions. Highlights include:

“A Very Lonely Soul”: A Tribute to Dracula’s Helen Chandler. Chandler is best known for playing the damsel-in-distress Mina in Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), opposite Bela Lugosi. Mank details Chandler’s life beyond the film, when alcoholism got the best of her and she drifted into obscurity.

Mad Jack Unleashed: Svengali and The Mad Genius. In the wake of Universal’s twin box office hits, Dracula and Frankenstein (both, 1931), other studios joined the horror bandwagon. Warner Bros. pegged its fortunes on two projects starring the legendary John Barrymore, Svengali and The Mad Genius (both, 1931). Mank chronicles each productions respective slides into disaster, doomed by the eccentric exploits of Barrymore.

The Mystery of Lionel Atwill: An Interview with the Son of the Late, Great Horror Star. Mank interviews Lionel Anthony Atwill, the son of Lionel Atwill. The latter was a featured performer in many of classic horror movies, most notably the mad sculptor in The Mystery of the Wax Museum (Warner Bros., 1933) and the one-armed inspector in The Son of Frankenstein (Universal, 1939). Offscreen, in 1941, Atwill found unwelcomed notoriety in a criminal conviction for perjury, related to orgies thrown at his L.A. home. This blackballed him in Hollywood until his death in 1946. His son, Lionel Anthony was just two years old. In chatting with Mank, however, the junior Atwill recalls his father’s legacy with affection and pride.

“Baby-Scarer!” Boris Karloff at Warner Bros., 1935-1939. After Karloff reached stardom at Universal, he negotiated a contract allowing him to work for other studios. For four years, he made a series of horror films at Warner Bros., the home of the gangster/social justice picture. Mank illuminates this period of Karloff’s career, that began so promisingly with The Walking Dead (dir. Michael Curtiz, 1936) and ended in animosity between he and the studio.

Libel and Old Lace. The Karloff saga continues with Mank recounting his journey with Arsenic and Old Lace from Broadway to Hollywood. Mank does a great job humanizing Karloff, shedding light on the icon’s initial stage fright, his savvy investment in the stage production, and his regrets in missing out on the Frank Capra film adaptation. Supporting players in this vastly entertaining saga include Bela Lugosi, Raymond Massey, Capra, and the award-winning writing/producing team of Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse.

Production Diaries: Cat People and The Curse of the Cat People. The Very Witching Time of Night is most enthralling when Mank details the production diaries of noted films. And few films have as intriguing a production history as Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People, and its sequel directed by Robert Wise. Both films were produced by Val Lewton, the resident horror auteur at RKO Radio Pictures. Despite tempestuous actors, minimal budgets, and censorship woes, Lewton, Tourneur, and Wise crafted two chillers that set standards in horror filmmaking. The photography, lighting, sound, and overall staging of Cat People, especially, is widely studied today.

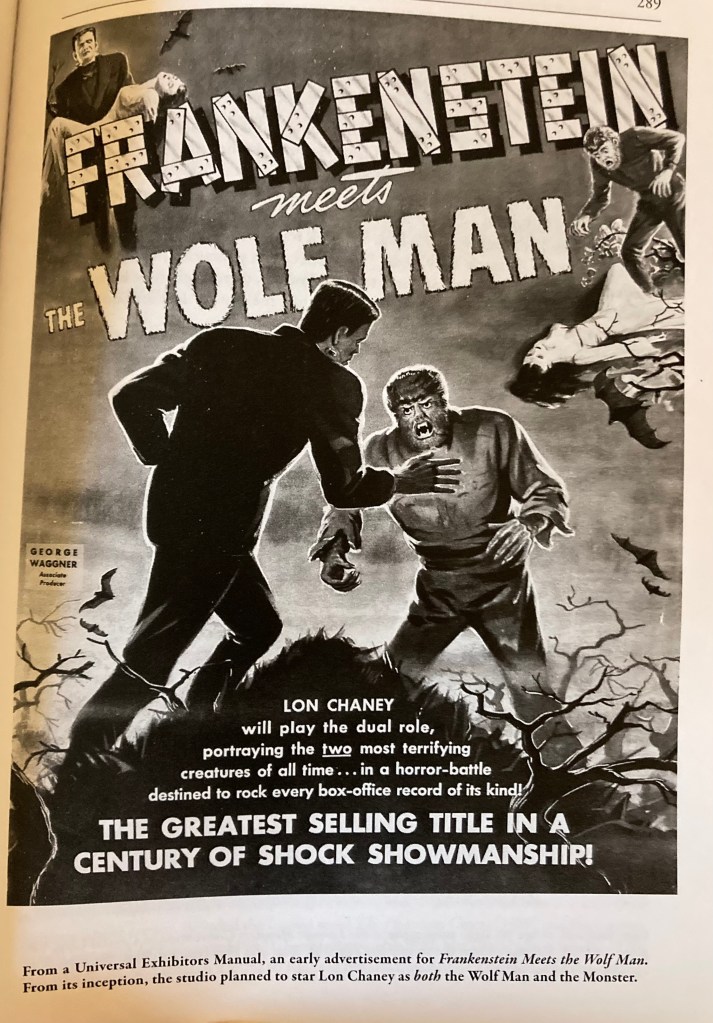

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man Revisited. In contrast to Cat People’‘s subtle artistry, Universal’s Wolf Man sequel is an over-the-top spectacle. Here too, Mank details the production behind Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, including its own set of headaches: Lon Chaney’s immature antics, Lionel Atwill’s aforementioned legal woes, and Bela Lugosi playing Frankenstein’s Monster. (The great irony, of course, is that Lugosi had turned down the part in 1931, thus opening the door for Karloff’s fame.)

John Carradine and His “Traveling Circus”. Who knew the horror actor was also a noted Shakespearean? Mank chronicles the painful efforts of Carradine to eschew Hollywood in pursuit of Broadway immortality. Carradine never reached the theatrical heights of his idol, John Barrymore, but for one brief season he played Hamlet, Shylock, and Othello in a West coast tour of his own financing. After his Shakespearean dreams collapsed, Carradine was confronted with a broken family, tattered financials, and damage to his reputation.

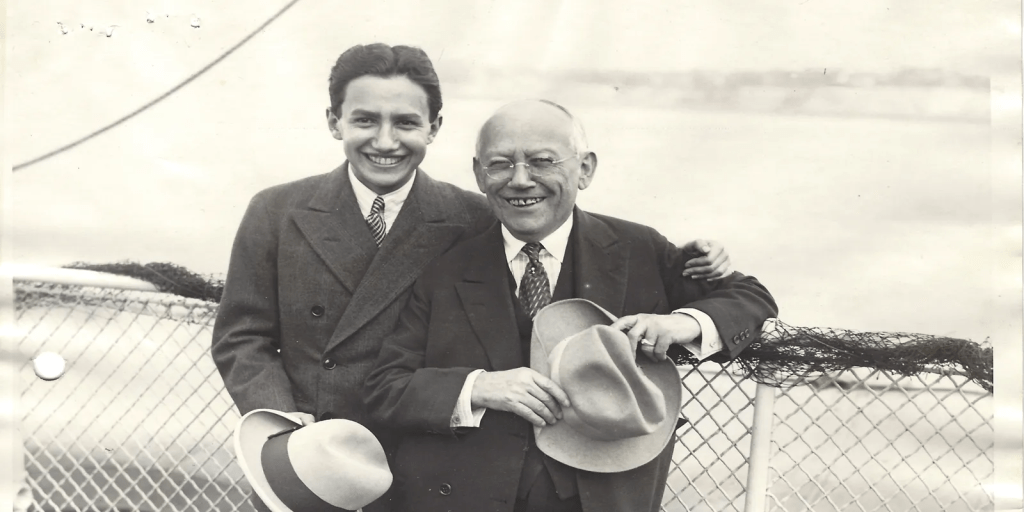

Junior Laemmle, Horror’s “Crown Prince” Producer. The final chapter of The Very Witching Time of Night is dedicated to the rise and fall of Carl Laemmle, Jr., whose father founded Universal Studios in 1912. Junior, meanwhile, was promoted to Head of Production in 1928, at just twenty years old. It was his mad genius behind the studio’s foundational run of horror films of the early 1930s: Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Black Cat, The Invisible Man, The Old Dark House, and Bride of Frankenstein – to name a few! But not all that glitters is gold, and Mank describes Junior’s battles with his father and brother-in-law for control of the studio; neither were fans of the horror genre or Junior’s tendency to spend money like water. Alas, the excess and infighting caught up with the Laemmle family in 1936, when they lost the studio to creditors. Junior never produced another film; he spent the rest of his life as a reclusive hypochondriac.

Gregory Mank’s The Very Witching Time of Night is a very introspective look into a rich aspect of Hollywood history – the Golden Age of horror films. Movie buffs will delight in the anecdotes Mank records from his interview subjects, as well as the copious behind-the-scenes notes the author provides. Less credible, but still entertaining, is the occasional conjecture Mank will indulge in; the infamous, but overblown rivalry between Lugosi and Karloff, for example. Nevertheless, if this book is your first exposure to Mank’s work, you will no doubt pick up another. Like the creatures in the films he chronicles, the classic horror genre is eternal and mysterious.

By Vincent S. Hannam

Don’t miss the next review – enter your email here!

And follow Camp Kaiju wherever you podcast!