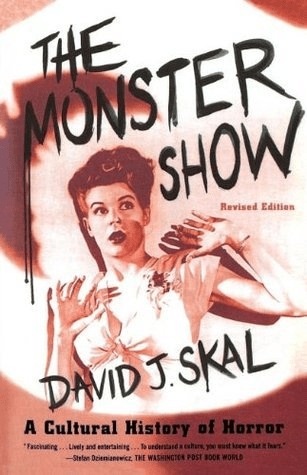

Horror movie writer, David J. Skal, put himself on the map with The Monster Show. Published in 1993, it followed his first book, Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Screen in 1990. With his second book, Skal ups the ante and explores not just Universal’s Dracula (1931), but America’s fascination with horror in general: movies, books, and even plastic surgery are all analyzed through this lens. Key works of art are discussed at length (such as Dracula [1931], Carrie [1974], and Interview With the Vampire [1976]) as well as the artists behind them (Tod Browning, Stephen King, Anne Rice). The Monster Show, however, is more than a list (like Skal’s TCM compendium Fright Favorites); rather, The Monster Show distinguishes itself as a psychological study of the cultural forces behind each work of horror. Skal lends enormous weight to the belief that all art is informed – if even subconsciously – by the culture of its time. Occasionally, Skal’s insight strays into overreaching conjecture, but his overall breezy – yet informed – style overcomes this criticism.

The strongest elements of the book come early with a deep dive into the horror films of the 1920s-1940s. Echoing his research for Hollywood Gothic, Skal robustly chronicles the post-World War I movie landscape of the Roaring Twenties. First in Weimar Germany with the Expressionistic works of F.W. Murnau and Conrad Veidt; then the transference of that aesthetic to Hollywood, as displayed in the films of Tod Browning, Lon Chaney, James Whale, Robert Florey, and Karl Freund. A running argument of The Monster Show is Skal’s observation that the physical monsters of this period,The Phantom of the Opera (1925), The Unknown (1927), Frankenstein (1931), and Freaks (1932) reflect the physical traumas of those veterans of the First World War. It is a profound revelation to consider the foundation of Western horror culture begins with the disfigurement of human lives in the early 20th century.

This initial cycle of horror movies (1920s-1940s) occupies the first half of The Monster Show. Beyond this time period, Skal moves into other mediums of horror, closely following the development of the Baby Boomers. The censorship of horror comics in the 1950s is given ample real estate, as is atomic anxiety, drive-in culture, and the resurgence of Universal’s early monsters in televisions programs like Vampira, The Munsters, and The Addams Family.

Topics grow decidedly less campy with the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s; take the sexual revolution for instance. As Skal notes, the Pill represented a sexual liberation for women to have control over their bodies; however, its creation by men can also represent the Patriarchy’s ulterior motives for encouraging such liberation. Skal finds parallels between birth/children anxiety in movies like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and It’s Alive (1974). The latter tying directly into the Thalidomide scourge of the 1960s, when a medicine for morning sickness was introduced with tragic side effects: children were being born without limbs. Skal once more brings the theme of disfigurement back to the monster movies of post-World War I. Other cultural anxieties reflected in popular horror include Vietnam and the zombie gore of George Romero and Tom Savini; religious critiques in the books of Stephen King; and the AIDS crisis reflected in vampire literature of the 1980s. These later chapters remain interesting but depart from the construct used earlier in The Monster Show; namely, the pointed exploration of the art itself.

This is where The Monster Show is weakest. The tonal difference between the first and second half of the book are subtle, but noticeable. Early on, Skal devotes much to the production of the films themselves, along with key insights into the filmmakers; later, this is abandoned and the result is a feeling of generality. The rise of plastic surgery in the 1980s, for example, is discussed at great length, but without a singular source of horror media to anchor it, it comes off more arm-chair psychologist than cultural historian. Skal argues that Western cultural obsession with cosmetic surgery has its roots in wartime disfigurement; the argument is promising, but his evidence for the claim is not (he points to the tabloid obsession over Michael Jackson’s evolving face composition). Perhaps Jackson is a viable horror personality because of “Thriller”? Skal overreaches in this respect, especially considering the bevy of horror films dealing explicitly with horrific bodily transformation. The Howling (1981), The Thing (1982), The Toxic Avenger (1984), and even Beetlejuice (1988) come to mind.

Further regarding the 1980s, there is hardly any mention of the rise of slashers as a tour de force on the pop psyche; the novel American Psycho (1991) by Bret Easton Ellis is given fair treatment, but there is only passing mention of Freddy Krueger and Michael Myers. Jason Voorhees is completely absent. It is an odd omission in a book titled A Cultural History of Horror when the sexually explicit slasher subgenre can be viewed as the cultural counter to Reagan Conservatism; a time reminiscent of Eisenhower’s 50s, when teenagers and censorship boards were engaged in a war for the nation’s morality. These are themes, of course, that reviewers can observe in hindsight; perhaps The Monster Show (1993) was simply written to soon after the 80s to appreciate the historical legacy.

Another weakness made evident by time, is Skal’s neglect of horror media by people of color. The benefit of the doubt may be given, however, considering the culture that The Horror Show examines is/was predominately white. Nevertheless, when Blacula (1973) is the only Black movie mentioned (and only as an aside), it raises the question, “why?” Skal misses an opportunity to examine the horror films of the Blaxploitation era when Black artists embraced newfound success in the mainstream. Conversely, uncomfortable portrayals of Black Americans by white filmmakers demand exploration; early voodoo-inspired zombie pictures like White Zombie (1932) and I Walked With a Zombie (1944) are prime examples.

Despite these dated elements, The Monster Show, is worth reading and horror fans will undoubtedly learn something new about their favorite monster movies. Enhancing the experience is Skal’s prose, which is effortlessly succinct and illuminating. Check it out at your local library, find it in a used-book store, or even do the Skal estate a solid and buy it new; either way, read it as a fabulous resource for your monster movie education.

UPDATE: The author would like to clarify, this is a review of the first edition of The Monster Show. It is unknown if subsequent revised editions address the aforementioned critiques.

by Vincent S. Hannam

Don’t miss the next review – enter your email here, and tell your friends about Camp Kaiju!