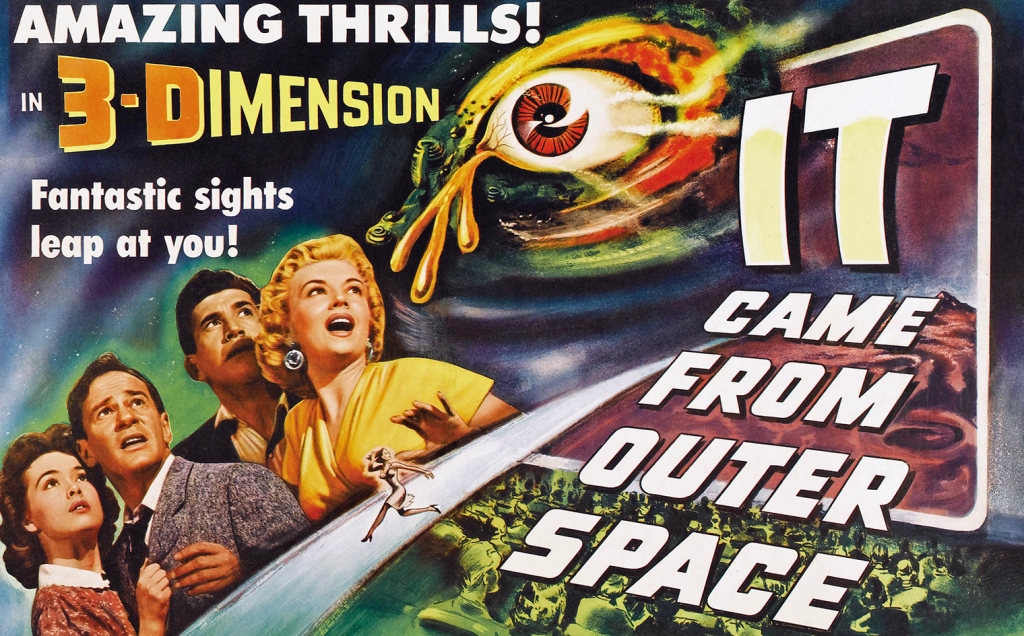

Over the next several months, Camp Kaiju will highlight the science fiction films of director Jack Arnold, whose filmography of the 1950s helped define the genre for the silver screen. Films like Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) continue to loom large over pop culture’s imagination; indeed, those films have arguably grown larger than the very person who directed them. Jack Arnold, therefore, deserves attention for being a genre director with an auteur’s flair. This series will examines several of Arnold’s films: his first science fiction movie It Came from Outer Space (1953), his widely-considered masterpiece, The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), and his final sci-fi outing, The Space Children (1958). Along the way, we will undoubtedly discuss the likes of the Gill-Man, Tarantula (1955) and even The Monolith Monsters (1957), on which Arnold was credited with the story.

Director: Jack Arnold

Screenplay: Harry Essex, based on an original film treatment by Ray Bradbury

Producer: William Alland

Cinematography: Clifford Stine

Editing: Paul Weatherwax

Music: Irving Gertz, Henry Mancini, Herman Stein

Select Cast: Richard Carlson, Barbara Rush, Charles Drake, Joe Sawyer, Russell Johnson, Kathleen Hughes, Dave Willock, Alan Dexter

Runtime: 81 minutes

Country of Origin: U.S.A.

U.S. Theatrical Release: June 5, 1953; Universal Pictures

The early 1950s saw the rise of science fiction as a dominant cinematic genre in the United States. The Gothic ghoulies that haunted screens of the 1930s and ’40s fell out of fashion after World War II. The U.S. had defeated the Nazis and vanquished those Eurocentric vampires and Germanic mad doctors. But soon other specters would fill the need for metaphorical adversaries, and in post-war America those would be Communists and atomic anxiety. Science fiction, as it turned out, was the ideal genre for filmmakers to visualize these worries as metaphorical monsters; invaders from another world could substitute a Red invasion and giant animals (and sometimes people) could ring the atomic alarm bell.

Between 1951-1953, cinemas were graced with science fiction classics like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) from 20th Century Fox; The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) from Warner Bros.; and Invaders from Mars (1953), also from 20th Century Fox. It was on this bandwagon that Universal Pictures jumped, with producer William Alland tapping contract director, Jack Arnold, to helm a Ray Bradbury tale of aliens crashing to Earth. The story was a film treatment called “The Meteor” that would become It Came from Outer Space; and while Bradbury would not be credited with the screenplay, his fingerprints are nevertheless present. As for Arnold, he was a perfect fit to bring out Bradbury’s trademark social messaging and poetic language.

Before 1953, Jack Arnold had one narrative film to his credit (Girls in the Night, a film noir); however, his documentary With These Hands (1950) was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. The documentary is about a retired laborer recounting his career in the garment industry in New York City in the early 20th century; it is a documentary, but it uses dramatization to bring historic events to life, and the loose story is tied together with a character-driven narrative. Not only does this device draw viewers into the story, but it effectively conveys the human-toll of union activism in the United States. Arnold uses With These Hands to document the long struggle for labor rights and in doing so, establishes his reputation as a socially-conscious director. Therefore, pairing Arnold with a writer like Bradbury, allowed the humanist instincts of both artists to rise above the low-expectations of a would-be B picture.

This is what makes It Came from Outer Space so unique. The movie is about aliens who crash their ship into the Arizona desert in a fiery blaze. The plummeting fireball is witnessed by amateur scientist John Putnam (Richard Carlson) and his romantic partner Ellen (Barbara Rush); together they investigate the scene of the crash, now a massive crater. Eager to study the remnants of the presumed-meteor, Putnam descends into the cavity; however, instead of a meteor, he finds an alien life form approaching from within its ship. But before contact is made, the unstable walls of the crater come crashing down. Putnam escapes but the ship is buried.

Ever the idealist, Putnam unabashedly tells Ellen and the authorities what he encountered. Their reactions serve as the conflict of the story; Sheriff Matt (Charles Drake) is outright contemptuous, Putnam’s mentor-in-science brushes off the claim, and even Ellen is dubious. Soon, however, the Sheriff comes around when strange phenomena begin to disrupt the town; meanwhile Putnam convenes with the aliens, who have holed up in an old mineshaft leading to their buried ship. There he discovers the extraterrestrials are not invaders, but hapless travelers whose ship has run aground on a hostile world. Nonetheless, they warn Putnam that despite their benign natures, they will not hesitate to defend themselves. As the Sheriff and a vindictive posse set out for the mine, Putnam must do all he can to avert a calamitous conflict.

Richard Carlson perfectly embodies the struggle Putnam faces in this community; he is an idealist surrounded by skeptics. He is constantly mocked by those who do not understand his erudite interests, and even those he trusts do not believe his story. Furthermore, he is often reminded by the townspeople that he is not one of them. (Putnam is a city slicker who has moved to the desert for peace and quiet.) Both he and the aliens are strangers in a strange land; they are also innocents falling victim to fearful prejudice. Embodying this prejudice is Charles Drake as Sheriff Matt. However, despite his antagonism toward Putnam, he only acts out of a desire to protect his community (especially Ellen, an old flame). Drake’s performance is therefore delightfully nuanced; we may not like the guy, but we can understand where he is coming from.

This level of awareness for human actions must be credited to Jack Arnold’s ability to understand the subtext of the script. A lesser director may have overlooked these notes of alienation (no pun intended), idealism in the face of hostility, or even choosing nonviolence in the face of conflict, and that version of It Came from Outer Space would have been fine; maybe not memorable, but fine. Thankfully, the Jack Arnold version of It Came from Outer Space remains memorable because here is a director using monsters to share his own ideals with a country openly hostile to socially-minded individuals. (McCarthyism was in full-force in 1953, with the House of Un-American Activities Committee actively targeting Hollywood.)

It Came from Outer Space was released in June, 1953. It was a box office hit and Barbara Rush won a Golden Globe for playing Ellen; and while modern critics overwhelmingly regard the film as a classic, it was initially met with lukewarm reviews. Critic A.H. Weiler wrote in The New York Times, “the adventure in which he [Richard Carlson] is involved is merely mildly diverting, not stupendous.” Indeed, Jack Arnold’s direction is understated throughout; their are few outright scares. But this is arguably the film’s strength, allowing Bradbury’s words to shine through; all the same, perhaps It Came From Outer Space is too understated compared to others in its field; perhaps the subtle poetry of the film is too easily overlooked amidst the comparative lack of action and thrills.

As the decade progressed, however, Arnold would refine this balance between philosophical musings and thrilling action. His next project, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, would prove a major milestone in this balancing act; not only for Jack Arnold the auteur, but for the legacy of horror cinema.

Don’t miss the next review – enter your email here!

And follow CAMP KAIJU wherever you podcast!

Further reading:

Housman, A. “How Director Jack Arnold Defined American Sci-Fi Movies”. Screen Rant. 2020.

Waas, J. “It Came from Outer Space”. Scifist – A Journey in Science Fiction Movies. 2021.